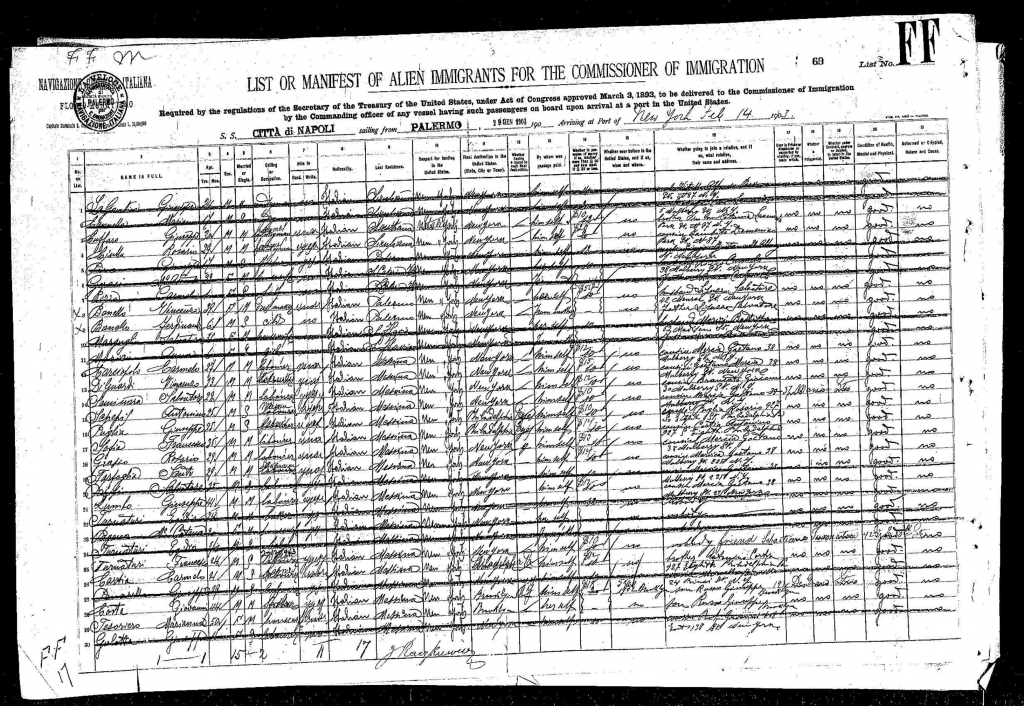

This is the ship’s manifest from February 14, 1903, the day my 21 year old grandfather arrived at Ellis Island. I have three other ships’ manifests, each showing the arrival date of each of my grandparents. They came from Germany, Hungary and Italy. I won’t bore you with the other three, but I have them.

If you scroll down to line 26, you’ll find my grandfather: Carmelo Cartia. You’ll see he was a farmer. You’ll see that he departed from Palermo and that he arrived with $10 in his pocket. You’ll see that his final destination was Philadelphia. You’ll see that he was going to join his brother, Antonio Cartia, who had arrived earlier.

And then other questions:

Was he ever in prison or supported by charity? (no)

Was he a polygamist? (no)

Was he was under contract to labor in the United States? (no)

What was the condition of his health, both physical and mental? (good)

Was he deformed or crippled? (no)

And having arrived at Ellis Island, each grandparent faced the same long wait and same scrutiny. They stood and sat for countless hours, watching those ahead of them. They watched families torn apart, as one member was refused while the others were allowed entry. They watched as white “X’s” were drawn with chalk on the clothing of those suspected of bringing illness into the country. They were poked and prodded and their intelligence tested with a list of questions. They met with a whole host of people, which meant they experienced a myriad of interactions: fear and kindness; anxiety and compassion.

And here’s the part that I find the most amazing: they came knowing no assistance was waiting for them in the United States; no promise of help. Short of scattered charities here and there, there was nothing else.

No federal assistance.

No food.

No housing.

No clothing.

There was no one waiting to sign them up for anything.

And to be an Italian immigrant, well, that was pretty much the bottom rung of the ladder. Italians were considered stupid. Dirty. Lazy. Dishonest.

And yet, they came, because of the ONE THING America did promise: opportunity. What they accomplished, if they succeeded in the American dream, it would be by the sweat of their brow, and the sweat of their brow alone.

They came not knowing English, but learn it they did. And speak it. Yes, they had to, but more importantly, they wanted to. They kept their traditions and cultures alive in their homes and communities but each shared the same desire: to fit in and “become American.” Most wanted to blend into society and become a part of the patchwork of the United States, a desire they instilled in their children. They didn’t want to stand out; they didn’t want to turn America into the country they came from. They embraced American principles and that indefinable THING that makes Americans well, American.

There were some, of course, who didn’t. The elder immigrants, too old to change and not really wanting to, like Mrs. Kremo, who lived next door to my grandparents’ house and had pictures of each of her deceased children IN THEIR CASKETS on her fireplace mantle. She was said to be some sort of Hungarian witch and she scared my dad well into his adulthood. Even 1500 miles away and 30 years later, he would still make a face and shudder when he spoke of her.

And as I reflect back to the stories shared with me by my parents and grandparents, and the firsthand Ellis Island accounts, I find it interesting how different things were. We were a young country then (still are) with wide open stretches of land to be developed and farmed and founded. We had space to fill and the country needed people. I don’t think anyone was really concerned with the word “jihad,” had they ever heard it to begin with.

Yes, the American Dream was open to all. Well, that’s not true. It was open unless you couldn’t or wouldn’t work. Then, things got a little trickier. See, the immigration policy of the time was to only allow entry to those who would not be a burden on the United States; those who would contribute to society and be “givers,” helping to grow this melting pot of a country. And if you were deemed unable or unwilling, there was a good chance you’d be sent back.

I can’t even imagine.

Fast forward to today. We are now a different time in our nation’s history. Some of the changes we’ve made in attitudes are great; some, not so much. We are more accepting, to be sure, and that’s a Good Thing, but sometimes TOO accepting for fear that if we aren’t, we will be labeled something unflattering.

People have become pawns to further agendas all over the world.

And I don’t know what will become of our immigration policy. I’m trying to maintain an open mind, and that fact alone has proved bothersome to many. I’ve seen a lot of misinformation spread by both sides. Thanks, social media. Emotions are high and when that happens, few stop to really research and investigate; they simply pick up a bullhorn and start screaming.

I wish it wasn’t that way.

The United States was always called a “melting pot:” a blend of different cultures and nationalities all swirled together into one people called: American. It’s one of the many things I’ve always loved that about this country. But my daughter shared with me the other day that it is now deemed incorrect to call the United States a “melting pot.” The new politically correct term is “salad bowl:” different cultures and nationalities residing in the same space, but no longer blending together. Each separate and distinct.

Think about that.

Is it any wonder we find ourselves in the mess we’re in?

xoxo

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.